PATTERNS OF PARALLEL PROGRAMMING

UNDERSTANDING AND APPLYING PARALLEL PATTERNS

WITH THE .NET FRAMEWORK 4 AND VISUAL C#

Stephen Toub

Parallel Computing Platform

Microsoft Corporation

Abstract

This document provides an in-depth tour of support in the Microsoft® .NET Framework 4 for parallel programming.

This includes an examination of common parallel patterns and how they’re implemented without and with this

new support, as well as best practices for developing parallel components utilizing parallel patterns.

Last Upd ated:

July 1, 2010

This material is provided for informational purposes only. Microsoft makes no warranties, express or implied.

©2010 Microsoft Corporation.

T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S

Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….3

Delightfully Parallel Loops ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………4

Fork/Join ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….36

Passing Data……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..49

Producer/Consumer ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….53

Aggregations …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….67

MapReduce………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………75

Dependencies …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..77

Data Sets of Unknown Size …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………88

Speculative Processing ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………94

Laziness ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………97

Shared State …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..105

Conclusion ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..118

Patterns of Parallel Programming Page 2

I N T R O D U C T I O N I N T R O D U C T I O N

Patterns are everywhere, yielding software development best practices and helping to seed new generations of

developers with immediate knowledge of established directions on a wide array of problem spaces. Patterns

represent successful (or in the case of anti-patterns, unsuccessful) repeated and common solutions developers

have applied time and again in particular architectural and programming domains. Over time, these tried and true

practices find themselves with names, stature, and variations, helping further to proliferate their application and

to jumpstart many a project.

Patterns don’t just manifest at the macro level. Whereas design patterns typically cover architectural structure or

methodologies, coding patterns and building blocks also emerge, representing typical ways of implementing a

specific mechanism. Such patterns typically become ingrained in our psyche, and we code with them on a daily

basis without even thinking about it. These patterns represent solutions to common tasks we encounter

repeatedly.

Of course, finding good patterns can happen only after many successful and failed attempts at solutions. Thus for

new problem spaces, it can take some time for them to gain a reputation. Such is where our industry lies today

with regards to patterns for parallel programming. While developers in high-performance computing have had to

develop solutions for supercomputers and clusters for decades, the need for such experiences has only recently

found its way to personal computing, as multi-core machines have become the norm for everyday users. As we

move forward with multi-core into the manycore era, ensuring that all software is written with as much parallelism

and scalability in mind is crucial to the future of the computing industry. This makes patterns in the parallel

computing space critical to that same future.

“In general, a ‘multi-core’ chip refers to eight or fewer homogeneous cores in one

microprocessor package, whereas a ‘manycore’ chip has more than eight possibly

heterogeneous cores in one microprocessor package. In a manycore system, all cores

share the resources and services, including memory and disk access, provided by the

operating system.” –The Manycore Shift, (Microsoft Corp., 2007)

In the .NET Framework 4, a slew of new support has been added to handle common needs in parallel

programming, to help developers tackle the difficult problem that is programming for multi-core and manycore.

Parallel programming is difficult for many reasons and is fraught with perils most developers haven’t had to

experience. Issues of races, deadlocks, livelocks, priority inversions, two-step dances, and lock convoys typically

have no place in a sequential world, and avoiding such issues makes quality patterns all the more important. This

new support in the .NET Framework 4 provides support for key parallel patterns along with building blocks to help

enable implementations of new ones that arise.

To that end, this document provides an in-depth tour of support in the .NET Framework 4 for parallel

programming, common parallel patterns and how they’re implemented without and with this new support, and

best practices for developing parallel components in this brave new world.

This document only minimally covers the subject of asynchrony for scalable, I/O-bound applications: instead, it

focuses predominantly on applications of CPU-bound workloads and of workloads with a balance of both CPU and

I/O activity. This document also does not cover Visual F# in Visual Studio 2010, which includes language-based

support for several key parallel patterns.

Patterns of Parallel Programming Page 3

D E L I G H T F U L L Y P A R A L L E L L O O P S D E L I G H T F U L L Y P A R A L L E L L O O P S

Arguably the most well-known parallel pattern is that befitting “Embarrassingly Parallel” algorithms. Programs that

fit this pattern are able to run well in parallel because the many individual operations being performed may

operate in relative independence, with few or no dependencies between operations such that they can be carried

out in parallel efficiently. It’s unfortunate that the “embarrassing” moniker has been applied to such programs, as

there’s nothing at all embarrassing about them. In fact, if more algorithms and problem domains mapped to the

embarrassing parallel domain, the software industry would be in a much better state of affairs. For this reason,

many folks have started using alternative names for this pattern, such as “conveniently parallel,” “pleasantly

parallel,” and “delightfully parallel,” in order to exemplify the true nature of these problems. If you find yourself

trying to parallelize a problem that fits this pattern, consider yourself fortunate, and expect that your

parallelization job will be much easier than it otherwise could have been, potentially even a “delightful” activity.

A significant majority of the work in many applications and algorithms is done through loop control constructs.

Loops, after all, often enable the application to execute a set of instructions over and over, applying logic to

discrete entities, whether those entities are integral values, such as in the case of a for loop, or sets of data, such

as in the case of a for each loop. Many languages have built-in control constructs for these kinds of loops,

Microsoft Visual C#® and Microsoft Visual Basic® being among them, the former with for and foreach keywords,

and the latter with For and For Each keywords. For problems that may be considered delightfully parallel, the

entities to be processed by individual iterations of the loops may execute concurrently: thus, we need a

mechanism to enable such parallel processing.

I M P L E M E N T I N G A P A R A L L E L L O O P I N G C O N S T R U C T

As delightfully parallel loops are such a predominant pattern, it’s really important to understand the ins and outs

of how they work, and all of the tradeoffs implicit to the pattern. To understand these concepts further, we’ll build

a simple parallelized loop using support in the .NET Framework 3.5, prior to the inclusion of the more

comprehensive parallelization support introduced in the .NET Framework 4.

First, we need a signature. To parallelize a for loop, we’ll implement a method that takes three parameters: a

lower-bound, an upper-bound, and a delegate for the loop body that accepts as a parameter an integral value to

represent the current iteration index (that delegate will be invoked once for each iteration). Note that we have

several options for the behavior of these parameters. With C# and Visual Basic, the vast majority of for loops are

written in a manner similar to the following:

C#

for (int i = 0; i < upperBound; i++)

{

// … loop body here

}

Visual Basic

For i As Integer = 0 To upperBound

‘ … loop body here

Next

Contrary to what a cursory read may tell you, these two loops are not identical: the Visual Basic loop will execute

one more iteration than will the C# loop. This is because Visual Basic treats the supplied upper-bound as inclusive,

Patterns of Parallel Programming Page 4

whereas we explicitly specified it in C# to be exclusive through our use of the less-than operator. For our purposes

here, we’ll follow suit to the C# implementation, and we’ll have the upper-bound parameter to our parallelized

loop method represent an exclusive upper-bound:

C#

public static void MyParallelFor(

int inclusiveLowerBound, int exclusiveUpperBound, Action<int> body);

Our implementation of this method will invoke the body of the loop once per element in the range

[inclusiveLowerBound,exclusiveUpperBound), and will do so with as much parallelization as it can muster. To

accomplish that, we first need to understand how much parallelization is possible.

Wisdom in parallel circles often suggests that a good parallel implementation will use one thread per core. After

all, with one thread per core, we can keep all cores fully utilized. Any more threads, and the operating system will

need to context switch between them, resulting in wasted overhead spent on such activities; any fewer threads,

and there’s no chance we can take advantage of all that the machine has to offer, as at least one core will be

guaranteed to go unutilized. This logic has some validity, at least for certain classes of problems. But the logic is

also predicated on an idealized and theoretical concept of the machine. As an example of where this notion may

break down, to do anything useful threads involved in the parallel processing need to access data, and accessing

data requires trips to caches or main memory or disk or the network or other stores that can cost considerably in

terms of access times; while such activities are in flight, a CPU may be idle. As such, while a good parallel

implementation may assume a default of one-thread-per-core, an open mindedness to other mappings can be

beneficial. For our initial purposes here, however, we’ll stick with the one-thread-per core notion.

With the .NET Framework, retrieving the number of logical processors is achieved

using the System.Environment class, and in particular its ProcessorCount property.

Under the covers, .NET retrieves the corresponding value by delegating to the

GetSystemInfo native function exposed from kernel32.dll.

This value doesn’t necessarily correlate to the number of physical processors or even

to the number of physical cores in the machine. Rather, it takes into account the

number of hardware threads available. As an example, on a machine with two

sockets, each with four cores, each with two hardware threads (sometimes referred

to as hyperthreads), Environment.ProcessorCount would return 16.

Starting with Windows 7 and Windows Server 2008 R2, the Windows operating

system supports greater than 64 logical processors, and by default (largely for legacy

application reasons), access to these cores is exposed to applications through a new

concept known as “processor groups.” The .NET Framework does not provide

managed access to the processor group APIs, and thus Environment.ProcessorCount

will return a value capped at 64 (the maximum size of a processor group), even if the

machine has a larger number of processors. Additionally, in a 32-bit process,

ProcessorCount will be capped further to 32, in order to map well to the 32-bit mask

used to represent processor affinity (a requirement that a particular thread be

scheduled for execution on only a specific subset of processors).

Patterns of Parallel Programming Page 5

Once we know the number of processors we want to target, and hence the number of threads, we can proceed to

create one thread per core. Each of those threads will process a portion of the input range, invoking the supplied

Action<int> delegate for each iteration in that range. Such processing requires another fundamental operation of

parallel programming, that of data partitioning. This topic will be discussed in greater depth later in this document;

suffice it to say, however, that partitioning is a distinguishing concept in parallel implementations, one that

separates it from the larger, containing paradigm of concurrent programming. In concurrent programming, a set of

independent operations may all be carried out at the same time. In parallel programming, an operation must first

be divided up into individual sub-operations so that each sub-operation may be processed concurrently with the

rest; that division and assignment is known as partitioning. For the purposes of this initial implementation, we’ll

use a simple partitioning scheme: statically dividing the input range into one range per thread.

Here is our initial implementation:

C#

public static void MyParallelFor(

int inclusiveLowerBound, int exclusiveUpperBound, Action<int> body)

{

// Determine the number of iterations to be processed, the number of

// cores to use, and the approximate number of iterations to process

// in each thread.

int size = exclusiveUpperBound -inclusiveLowerBound;

int numProcs = Environment.ProcessorCount;

int range = size / numProcs;

// Use a thread for each partition. Create them all,

// start them all, wait on them all.

var threads = new List<Thread>(numProcs);

for (int p = 0; p < numProcs; p++)

{

int start = p * range + inclusiveLowerBound;

int end = (p == numProcs -1) ?

exclusiveUpperBound : start + range;

threads.Add(new Thread(() => {

for (int i = start; i < end; i++) body(i);

}));

}

foreach (var thread in threads) thread.Start();

foreach (var thread in threads) thread.Join();

}

There are several interesting things to note about this implementation. One is that for each range, a new thread is

utilized. That thread exists purely to process the specified partition, and then it terminates. This has several

positive and negative implications. The primary positive to this approach is that we have dedicated threading

resources for this loop, and it is up to the operating system to provide fair scheduling for these threads across the

system. This positive, however, is typically outweighed by several significant negatives. One such negative is the

cost of a thread. By default in the .NET Framework 4, a thread consumes a megabyte of stack space, whether or

not that space is used for currently executing functions. In addition, spinning up a new thread and tearing one

down are relatively costly actions, especially if compared to the cost of a small loop doing relatively few iterations

and little work per iteration. Every time we invoke our loop implementation, new threads will be spun up and torn

down.

Patterns of Parallel Programming Page 6

There’s another, potentially more damaging impact: oversubscription. As we move forward in the world of multicore

and into the world of manycore, parallelized components will become more and more common, and it’s quite

likely that such components will themselves be used concurrently. If such components each used a loop like the

above, and in doing so each spun up one thread per core, we’d have two components each fighting for the

machine’s resources, forcing the operating system to spend more time context switching between components.

Context switching is expensive for a variety of reasons, including the need to persist details of a thread’s execution

prior to the operating system context switching out the thread and replacing it with another. Potentially more

importantly, such context switches can have very negative effects on the caching subsystems of the machine.

When threads need data, that data needs to be fetched, often from main memory. On modern architectures, the

cost of accessing data from main memory is relatively high compared to the cost of running a few instructions over

that data. To compensate, hardware designers have introduced layers of caching, which serve to keep small

amounts of frequently-used data in hardware significantly less expensive to access than main memory. As a thread

executes, the caches for the core on which it’s executing tend to fill with data appropriate to that thread’s

execution, improving its performance. When a thread gets context switched out, the caches will shift to containing

data appropriate to that new thread. Filling the caches requires more expensive trips to main memory. As a result,

the more context switches there are between threads, the more expensive trips to main memory will be required,

as the caches thrash on the differing needs of the threads using them. Given these costs, oversubscription can be a

serious cause of performance issues. Luckily, the new concurrency profiler views in Visual Studio 2010 can help to

identify these issues, as shown here:

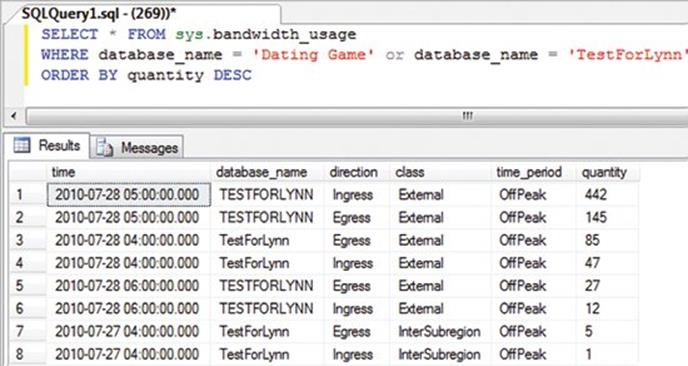

In this screenshot, each horizontal band represents a thread, with time on the x-axis. Green is execution time, red

is time spent blocked, and yellow is time where the thread could have run but was preempted by another thread .

The more yellow there is, the more oversubscription there is hurting performance.

To compensate for these costs associated with using dedicated threads for each loop, we can resort to pools of

threads. The system can manage the threads in these pools, dispatching the threads to access work items queued

for their processing, and then allowing the threads to return to the pool rather than being torn down. This

addresses many of the negatives outlined previously. As threads aren’t constantly being created and torn down,

the cost of their life cycle is amortized over all the work items they process. Moreover, the manager of the thread

pool can enforce an upper-limit on the number of threads associated with the pool at any one time, placing a limit

on the amount of memory consumed by the threads, as well as on how much oversubscription is allowed.

Ever since the .NET Framework 1.0, the System.Threading.ThreadPool class has provided just such a thread pool,

and while the implementation has changed from release to release (and significantly so for the .NET Framework 4),

the core concept has remained constant: the .NET Framework maintains a pool of threads that service work items

provided to it. The main method for doing this is the static QueueUserWorkItem. We can use that support in a

revised implementation of our parallel for loop:

Patterns of Parallel Programming Page 7

C#

public static void MyParallelFor(

int inclusiveLowerBound, int exclusiveUpperBound, Action<int> body)

{

// Determine the number of iterations to be processed, the number of

// cores to use, and the approximate number of iterations to process in

// each thread.

int size = exclusiveUpperBound -inclusiveLowerBound;

int numProcs = Environment.ProcessorCount;

int range = size / numProcs;

// Keep track of the number of threads remaining to complete.

int remaining = numProcs;

using (ManualResetEvent mre = new ManualResetEvent(false))

{

// Create each of the threads.

for (int p = 0; p < numProcs; p++)

{

int start = p * range + inclusiveLowerBound;

int end = (p == numProcs -1) ?

exclusiveUpperBound : start + range;

ThreadPool.QueueUserWorkItem(delegate {

for (int i = start; i < end; i++) body(i);

if (Interlocked.Decrement(ref remaining) == 0) mre.Set();

});

}

// Wait for all threads to complete.

mre.WaitOne();

}

}

This removes the inefficiencies in our application related to excessive thread creation and tear down, and it

minimizes the possibility of oversubscription. However, this inefficiency was just one problem with the

implementation: another potential problem has to do with the static partitioning we employed. For workloads that

entail the same approximate amount of work per iteration, and when running on a relatively “quiet”

machine

(meaning a machine doing little else besides the target workload), static partitioning represents an effective and

efficient way to partition our data set. However, if the workload is not equivalent for each iteration, either due to

the nature of the problem or due to certain partitions completing more slowly due to being preempted by other

significant work on the system, we can quickly find ourselves with a load imbalance. The pattern of a loadimbalance

is very visible in the following visualization as rendered by the concurrency profiler in Visual Studio

2010.

Patterns of Parallel Programming Page 8

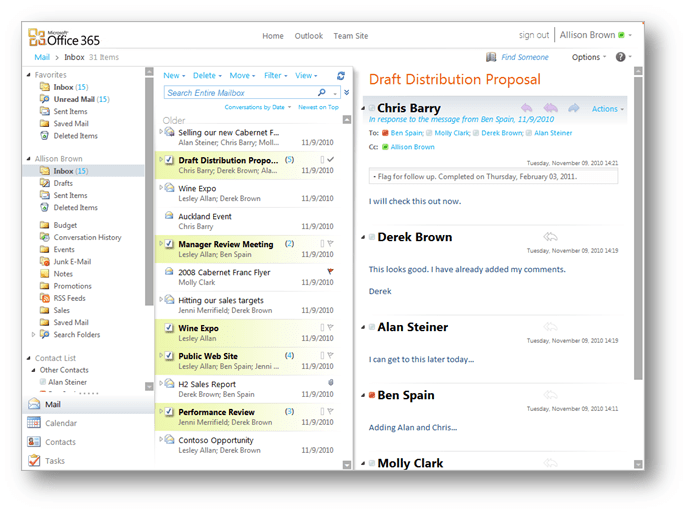

In this output from the profiler, the x-axis is time and the y-axis is the number of cores utilized at that time in the

application’s executions. Green is utilization by our application, yellow is utilization by another application, red is

utilization by a system process, and grey is idle time. This trace resulted from the unfortunate assignment of

different amounts of work to each of the partitions; thus, some of those partitions completed processing sooner

than the others. Remember back to our assertions earlier about using fewer threads than there are cores to do

work? We’ve now degraded to that situation, in that for a portion of this loop’s execution, we were executing with

fewer cores than were available.

By way of example, let’s consider a parallel loop from 1 to 12 (inclusive on both ends), where each iteration does N

seconds of work with N defined as the loop iteration value (that is, iteration #1 will require 1 second of

computation, iteration #2 will require two seconds, and so forth). All in all, this loop will require ((12*13)/2) == 78

seconds of sequential processing time. In an ideal loop implementation on a dual core system, we could finish this

loop’s processing in 39 seconds. This could be accomplished by having one core process iterations 6, 10, 11, and

12, with the other core processing the rest of the iterations.

123456789101112

However, with the static partitioning scheme we’ve employed up until this point, one core will be assigned the

range [1,6] and the other the range [7,12].

123456789101112

Patterns of Parallel Programming Page 9

As such, the first core will have 21 seconds worth of work, leaving the latter core 57 seconds worth of work. Since

the loop isn’t finished until all iterations have been processed, our loop’s processing time is limited by the

maximum processing time of each of the two partitions, and thus our loop completes in 57 seconds instead of the

aforementioned possible 39 seconds. This represents an approximate 50 percent decrease in potential

performance, due solely to an inefficient partitioning. Now you can see why partitioning has such a fundamental

place in parallel programming.

Different variations on static partitioning are possible. For example, rather than assigning ranges, we could use a

form of round-robin, where each thread has a unique identifier in the range [0,# of threads), and where each

thread processes indices from the loop where the index mod the number of threads matches the thread’s

identifier. For example, with the iteration space [0,12) and with four threads, thread #0 would process iteration

values 0, 3, 6, and 9; thread #1 would process iteration values 1, 4, 7, and 10; and so on. If we were to apply this

kind of round-robin partitioning to the previous example, instead of one thread taking 21 seconds and the other

taking 57 seconds, one thread would require 36 seconds and the other 42 seconds, resulting in a much smaller

discrepancy from the optimal runtime of 38 seconds.

123456789101112

To do the best static partitioning possible, you need to be able to accurately predict ahead of time how long all the

iterations will take. That’s rarely feasible, resulting in a need for a more dynamic partitioning, where the system

can adapt to changing workloads quickly. We can address this by shifting to the other end of the partitioning

tradeoffs spectrum, with as much load-balancing as possible.

Spectrum of Partitioning

TradeoffsFully

StaticFully

DynamicMore Load-BalancingLess Synchronization

To do that, rather than pushing to each of the threads a given set of indices to process, we can have the threads

compete for iterations. We employ a pool of the remaining iterations to be processed, which initially starts filled

with all iterations. Until all of the iterations have been processed, each thread goes to the iteration pool, removes

an iteration value, processes it, and then repeats. In this manner, we can achieve in a greedy fashion an

approximation for the optimal level of load-balancing possible (the true optimum could only be achieved with a

priori knowledge of exactly how long each iteration would take). If a thread gets stuck processing a particular long

iteration, the other threads will compensate by processing work from the pool in the meantime. Of course, even

with this scheme you can still find yourself with a far from optimal partitioning (which could occur if one thread

happened to get stuck with several pieces of work significantly larger than the rest), but without knowledge of how

much processing time a given piece of work will require, there’s little more that can be done.

Patterns of Parallel Programming Page 10

Here’s an example implementation that takes load-balancing to this extreme. The pool of iteration values is

maintained as a single integer representing the next iteration available, and the threads involved in the processing

“remove items” by atomically incrementing this integer:

C#

public static void MyParallelFor(

int inclusiveLowerBound, int exclusiveUpperBound, Action<int> body)

{

// Get the number of processors, initialize the number of remaining

// threads, and set the starting point for the iteration.

int numProcs = Environment.ProcessorCount;

int remainingWorkItems = numProcs;

int nextIteration = inclusiveLowerBound;

using (ManualResetEvent mre = new ManualResetEvent(false))

{

// Create each of the work items.

for (int p = 0; p < numProcs; p++)

{

ThreadPool.QueueUserWorkItem(delegate

{

int index;

while ((index = Interlocked.Increment(

ref nextIteration) -1) < exclusiveUpperBound)

{

body(index);

}

if (Interlocked.Decrement(ref remainingWorkItems) == 0)

mre.Set();

});

}

// Wait for all threads to complete.

mre.WaitOne();

}

}

This is not a panacea, unfortunately. We’ve gone to the other end of the spectrum, trading quality load-balancing

for additional overheads. In our previous static partitioning implementations, threads were assigned ranges and

were then able to process those ranges completely independently from the other threads. There was no need to

synchronize with other threads in order to determine what to do next, because every thread could determine

independently what work it needed to get done. For workloads that have a lot of work per iteration, the cost of

synchronizing between threads so that each can determine what to do next is negligible. But for workloads that do

very little work per iteration, that synchronization cost can be so expensive (relatively) as to overshadow the actual

work being performed by the loop. This can make it more expensive to execute in parallel than to execute serially.

Consider an analogy: shopping with some friends at a grocery store. You come into

the store with a grocery list, and you rip the list into one piece per friend, such that

every friend is responsible for retrieving the elements on his or her list. If the amount

of time required to retrieve the elements on each list is approximately the same as on

every other list, you’ve done a good job of partitioning the work amongst your team,

and will likely find that your time at the store is significantly less than if you had done

Patterns of Parallel Programming Page 11

all of the shopping yourself. But now suppose that each list is not well balanced, with

all of the items on one friend’s list spread out over the entire store, while all of the

items on another friend’s list are concentrated in the same aisle. You could address

this inequity by assigning out one element at a time. Every time a friend retrieves a

food item, he or she brings it back to you at the front of the store and determines in

conjunction with you which food item to retrieve next. If a particular food item takes

a particularly long time to retrieve, such as ordering a custom cut piece of meat at

the deli counter, the overhead of having to go back and forth between you and the

merchandise may be negligible. For simply retrieving a can from a shelf, however, the

overhead of those trips can be dominant, especially if multiple items to be retrieved

from a shelf were near each other and could have all been retrieved in the same trip

with minimal additional time. You could spend so much time (relatively) parceling out

work to your friends and determining what each should buy next that it would be

faster for you to just grab all of the food items in your list yourself.

Of course, we don’t need to pick one extreme or the other. As with most patterns, there are variations on themes.

For example, in the grocery store analogy, you could have each of your friends grab several items at a time, rather

than grabbing one at a time. This amortizes the overhead across the size of a batch, while still having some amount

of dynamism:

C#

public static void MyParallelFor(

int inclusiveLowerBound, int exclusiveUpperBound, Action<int> body)

{

// Get the number of processors, initialize the number of remaining

// threads, and set the starting point for the iteration.

int numProcs = Environment.ProcessorCount;

int remainingWorkItems = numProcs;

int nextIteration = inclusiveLowerBound;

const int batchSize = 3;

using (ManualResetEvent mre = new ManualResetEvent(false)) {

// Create each of the work items.

for (int p = 0; p < numProcs; p++) {

ThreadPool.QueueUserWorkItem(delegate {

int index;

while ((index = Interlocked.Add(

ref nextIteration, batchSize) -batchSize)

< exclusiveUpperBound)

{

// In a real implementation, we’d need to handle

// overflow on this arithmetic.

int end = index + batchSize;

if (end >= exclusiveUpperBound) end = exclusiveUpperBound;

for (int i = index; i < end; i++) body(i);

}

if (Interlocked.Decrement(ref remainingWorkItems) == 0)

mre.Set();

});

}

// Wait for all threads to complete

mre.WaitOne();

Patterns of Parallel Programming Page 12

}

}

No matter what tradeoffs you make between overheads and load-balancing, they are tradeoffs. For a particular

problem, you might be able to code up a custom parallel loop algorithm mapping to this pattern that suits your

particular problem best. That could result in quite a bit of custom code, however. In general, a good solution is one

that provides quality results for most problems, minimizing overheads while providing sufficient load-balancing,

and the .NET Framework 4 includes just such an implementation in the new System.Threading.Tasks.Parallel class.

P A R A L L E L . F O R

As delightfully parallel problems represent one of the most common patterns in parallel programming, it’s natural

that when support for parallel programming is added to a mainstream library, support for delightfully parallel

loops is included. The .NET Framework 4 provides this in the form of the static Parallel class in the new

System.Threading.Tasks namespace in mscorlib.dll. The Parallel class provides just three methods, albeit each

with several overloads. One of these methods is For, providing multiple signatures, one of which is almost identical

to the signature for MyParallelFor shown previously:

C#

public static ParallelLoopResult For(

int fromInclusive, int toExclusive, Action<int> body);

As with our previous implementations, the For method accepts three parameters: an inclusive lower-bound, an

exclusive upper-bound, and a delegate to be invoked for each iteration. Unlike our implementations, it also returns

a ParallelLoopResult value type, which contains details on the completed loop; more on that later.

Internally, the For method performs in a manner similar to our previous implementations. By default, it uses work

queued to the .NET Framework ThreadPool to execute the loop, and with as much parallelism as it can muster, it

invokes the provided delegate once for each iteration. However, Parallel.For and its overload set provide a whole

lot more than this:

.

Exception handling. If one iteration of the loop throws an exception, all of the threads participating in the

loop attempt to stop processing as soon as possible (by default, iterations currently executing will not be

interrupted, but the loop control logic tries to prevent additional iterations from starting). Once all

processing has ceased, all unhandled exceptions are gathered and thrown in aggregate in an

AggregateException instance. This exception type provides support for multiple “inner exceptions,”

whereas most .NET Framework exception types support only a single inner exception. For more

information about AggregateException, see http://msdn.microsoft.com/magazine/ee321571.aspx.

.

Breaking out of a loop early. This is supported in a manner similar to the break keyword in C# and the

Exit For construct in Visual Basic. Support is also provided for understanding whether the current

iteration should abandon its work because of occurrences in other iterations that will cause the loop to

end early. This is the primary reason for the ParallelLoopResult return value, shown in the Parallel.For

signature, which helps a caller to understand if a loop ended prematurely, and if so, why.

.

Long ranges. In addition to overloads that support working with Int32-based ranges, overloads are

provided for working with Int64-based ranges.

.

Thread-local state. Several overloads provide support for thread-local state. More information on this

support will be provided later in this document in the section on aggregation patterns.

Patterns of Parallel Programming Page 13

.

Configuration options. Multiple aspects of a loop’s execution may be controlled, including limiting the

number of threads used to process the loop.

.

Nested parallelism. If you use a Parallel.For loop within another Parallel.For loop, they coordinate with

each other to share threading resources. Similarly, it’s ok to use two Parallel.For loops concurrently, as

they’ll work together to share threading resources in the underlying pool rather than both assuming th ey

own all cores on the machine.

.

Dynamic thread counts. Parallel.For was designed to accommodate workloads that change in complexity

over time, such that some portions of the workload may be more compute-bound than others. As such, it

may be advantageous to the processing of the loop for the number of threads involved in the processing

to change over time, rather than being statically set, as was done in all of our implementations shown

earlier.

.

Efficient load balancing. Parallel.For supports load balancing in a very sophisticated manner, much more

so than the simple mechanisms shown earlier. It takes into account a large variety of potential workloads

and tries to maximize efficiency while minimizing overheads. The partitioning implementation is based on

a chunking mechanism where the chunk size increases over time. This helps to ensure quality load

balancing when there are only a few iterations, while minimizing overhead when there are many. In

addition, it tries to ensure that most of a thread’s iterations are focused in the same region of the

iteration space in order to provide high cache locality.

Parallel.For is applicable to a wide-range of delightfully parallel problems, serving as an implementation of this

quintessential pattern. As an example of its application, the parallel programming samples for the .NET Framework

4 (available at http://code.msdn.microsoft.com/ParExtSamples) include a ray tracer. Here’s a screenshot:

Ray tracing is fundamentally a delightfully parallel problem. Each individual pixel in the image is generated by firing

an imaginary ray of light, examining the color of that ray as it bounces off of and through objects in the scene, and

storing the resulting color. Every pixel is thus independent of every other pixel, allowing them all to be processed

in parallel. Here are the relevant code snippets from that sample:

C#

void RenderSequential(Scene scene, Int32[] rgb)

{

Camera camera = scene.Camera;

for (int y = 0; y < screenHeight; y++)

{

int stride = y * screenWidth;

for (int x = 0; x < screenWidth; x++)

Patterns of Parallel Programming Page 14

{

Color color = TraceRay(

new Ray(camera.Pos, GetPoint(x, y, camera)), scene, 0);

rgb[x + stride] = color.ToInt32();

}

}

}

void RenderParallel(Scene scene, Int32[] rgb)

{

Camera camera = scene.Camera;

Parallel.For(0, screenHeight, y =>

{

int stride = y * screenWidth;

for (int x = 0; x < screenWidth; x++)

{

Color color = TraceRay(

new Ray(camera.Pos, GetPoint(x, y, camera)), scene, 0);

rgb[x + stride] = color.ToInt32();

}

});

}

Notice that there are very few differences between the sequential and parallel implementation, limited only to

changing the C# for and Visual Basic For language constructs into the Parallel.For method call.

P A R A L L E L . F O R E A C H

A for loop is a very specialized loop. Its purpose is to iterate through a specific kind of data set, a data set made up

of numbers that represent a range. The more generalized concept is iterating through any data set, and constructs

for such a pattern exist in C# with the foreach keyword and in Visual Basic with the For Each construct.

Consider the following for loop:

C#

for(int i=0; i<10; i++)

{

// … Process i.

}

Using the Enumerable class from LINQ, we can generate an IEnumerable<int> that represents the same range, and

iterate through that range using a foreach:

C#

foreach(int i in Enumerable.Range(0, 10))

{

// … Process i.

}

We can accomplish much more complicated iteration patterns by changing the data returned in the enumerable.

Of course, as it is a generalized looping construct, we can use a foreach to iterate through any enumerable data

set. This makes it very powerful, and a parallelized implementation is similarly quite powerful in the parallel realm.

As with a parallel for, a parallel for each represents a fundamental pattern in parallel programming.

Patterns of Parallel Programming Page 15

Implementing a parallel for each is similar in concept to implementing a parallel for. You need multiple threads to

process data in parallel, and you need to partition the data, assigning the partitions to the threads doing the

processing. In our dynamically partitioned MyParallelFor implementation, the data set remaining was represented

by a single integer that stored the next iteration. In a for each implementation, we can store it as an

IEnumerator<T> for the data set. This enumerator must be protected by a critical section so that only one thread

at a time may mutate it. Here is an example implementation:

C#

public static void MyParallelForEach<T>(

IEnumerable<T> source, Action<T> body)

{

int numProcs = Environment.ProcessorCount;

int remainingWorkItems = numProcs;

using (var enumerator = source.GetEnumerator())

{

using (ManualResetEvent mre = new ManualResetEvent(false))

{

// Create each of the work items.

for (int p = 0; p < numProcs; p++)

{

ThreadPool.QueueUserWorkItem(delegate

{

// Iterate until there’s no more work.

while (true)

{

// Get the next item under a lock,

// then process that item.

T nextItem;

lock (enumerator)

{

if (!enumerator.MoveNext()) break;

nextItem = enumerator.Current;

}

body(nextItem);

}

if (Interlocked.Decrement(ref remainingWorkItems) == 0)

mre.Set();

});

}

// Wait for all threads to complete.

mre.WaitOne();

}

}

}

As with the MyParallelFor implementations shown earlier, there are lots of implicit tradeoffs being made in this

implementation, and as with the MyParallelFor, they all come down to tradeoffs between simplicity, overheads,

and load balancing. Taking locks is expensive, and this implementation is taking and releasing a lock for each

element in the enumerable; while costly, this does enable the utmost in load balancing, as every thread only grabs

one item at a time, allowing other threads to assist should one thread run into an unexpectedly expensive

element. We could tradeoff some cost for some load balancing by retrieving multiple items (rather than just one)

while holding the lock. By acquiring the lock, obtaining multiple items from the enumerator, and then releasing the

Patterns of Parallel Programming Page 16

lock, we amortize the cost of acquisition and release over multiple elements, rather than paying the cost for each

element. This benefit comes at the expense of less load balancing, since once a thread has grabbed several items,

it is responsible for processing all of those items, even if some of them happen to be more expensive than the bulk

of the others.

We can decrease costs in other ways, as well. For example, the implementation shown previously always uses the

enumerator’s MoveNext/Current support, but it might be the case that the source input IEnumerable<T> also

implements the IList<T> interface, in which case the implementation could use less costly partitioning, such as that

employed earlier by MyParallelFor:

C#

public static void MyParallelForEach<T>(IEnumerable<T> source, Action<T> body)

{

IList<T> sourceList = source as IList<T>;

if (sourceList != null)

{

// This assumes the IList<T> implementation’s indexer is safe

// for concurrent get access.

MyParallelFor(0, sourceList.Count, i => body(sourceList[i]));

}

else

{

// …

}

}

As with Parallel.For, the .NET Framework 4’s Parallel class provides support for this pattern, in the form of the

ForEach method. Overloads of ForEach provide support for many of the same things for which overloads of For

provide support, including breaking out of loops early, sophisticated partitioning, and thread count dynamism. The

simplest overload of ForEach provides a signature almost identical to the signature shown above:

C#

public static ParallelLoopResult ForEach<TSource>(

IEnumerable<TSource> source, Action<TSource> body);

As an example application, consider a Student record that contains a settable GradePointAverage property as well

as a readable collection of Test records, each of which has a grade and a weight. We have a set of such student

records, and we want to iterate through each, calculating each student’s grades based on the associated tests.

Sequentially, the code looks as follows:

C#

foreach (var student in students)

{

student.GradePointAverage =

student.Tests.Select(test => test.Grade * test.Weight).Sum();

}

To parallelize this, we take advantage of Parallel.ForEach:

C#

Parallel.ForEach(students, student =>

{

Patterns of Parallel Programming Page 17

student.GradePointAverage =

student.Tests.Select(test => test.Grade * test.Weight).Sum();

});

P R O C E S S I N G N O N -I N T E G R A L R A N G E S

The Parallel class in the .NET Framework 4 provides overloads for working with ranges of Int32 and Int64 values.

However, for loops in languages like C# and Visual Basic can be used to iterate through non-integral ranges.

Consider a type Node<T> that represents a linked list:

C#

class Node<T>

{

public Node<T> Prev, Next;

public T Data;

}

Given an instance head of such a Node<T>, we can use a for loop to iterate through the list:

C#

for(Node<T> i = head; i != null; i = i.Next)

{

// … Process node i.

}

Parallel.For does not contain overloads for working with Node<T>, and Node<T> does not implement

IEnumerable<T>, preventing its direct usage with Parallel.ForEach. To compensate, we can use C# iterators to

create an Iterate method which will yield an IEnumerable<T> to iterate through the Node<T>:

C#

public static IEnumerable<Node<T>> Iterate(Node<T> head)

{

for (Node<T> i = head; i != null; i = i.Next)

{

yield return i;

}

}

With such a method in hand, we can now use a combination of Parallel.ForEach and Iterate to approximate a

Parallel.For implementation that does work with Node<T>:

C#

Parallel.ForEach(Iterate(head), i =>

{

// … Process node i.

});

This same technique can be applied to a wide variety of scenarios. Keep in mind, however, that the

IEnumerator<T> interface isn’t thread-safe, which means that Parallel.ForEach needs to take locks when accessing

the data source. While ForEach internally uses some smarts to try to amortize the cost of such locks over the

Patterns of Parallel Programming Page 18

processing, this is still overhead that needs to be overcome by more work in the body of the ForEach in order for

good speedups to be achieved.

Parallel.ForEach has optimizations used when working on data sources that can be indexed into, such as lists and

arrays, and in those cases the need for locking is decreased (this is similar to the example implementation shown

previously, where MyParallelForEach was able to use MyParallelFor in processing an IList<T>). Thus, even though

there is both time and memory cost associated with creating an array from an enumerable, performance may

actually be improved in some cases by transforming the iteration space into a list or an array, which can be done

using LINQ. For example:

C#

Parallel.ForEach(Iterate(head).ToArray(), i =>

{

// … Process node i.

});

The format of a for construct in C# and a For in Visual Basic may also be generalized into a generic Iterate method:

C#

public static IEnumerable<T> Iterate<T>(

Func<T> initialization, Func<T, bool> condition, Func<T, T> update)

{

for (T i = initialization(); condition(i); i = update(i))

{

yield return i;

}

}

While incurring extra overheads for all of the delegate invocations, this now also provides a generalized

mechanism for iterating. The Node<T> example can be re-implemented as follows:

C#

Parallel.ForEach(Iterate(() => head, i => i != null, i => i.Next), i =>

{

// … Process node i.

});

B R E A K I N G O U T O F L O O P S E A R L Y

Exiting out of loops early is a fairly common pattern, one that doesn’t go away when parallelism is introduced. To

help simplify these use cases, the Parallel.For and Parallel.ForEach methods support several mechanisms for

breaking out of loops early, each of which has different behaviors and targets different requirements.

PLANNED EXIT

Patterns of Parallel Programming Page 19

Several overloads of Parallel.For and Parallel.ForEach pass a ParallelLoopState instance to the body delegate.

Included in this type’s surface area are four members relevant to this discussion: methods Stop and Break, and

properties IsStopped and LowestBreakIteration.

When an iteration calls Stop, the loop control logic will attempt to prevent additional iterations of the loop from

starting. Once there are no more iterations executing, the loop method will return successfully (that is, without an

exception). The return type of Parallel.For and Parallel.ForEach is a ParallelLoopResult value type: if Stop caused

the loop to exit early, the result’s IsCompleted property will return false.

C#

ParallelLoopResult loopResult =

Parallel.For(0, N, (int i, ParallelLoopState loop) =>

{

// …

if (someCondition)

{

loop.Stop();

return;

}

// …

});

Console.WriteLine(“Ran to completion: ” + loopResult.IsCompleted);

For long running iterations, the IsStopped property enables one iteration to detect when another iteration has

called Stop in order to bail earlier than it otherwise would:

C#

ParallelLoopResult loopResult =

Parallel.For(0, N, (int i, ParallelLoopState loop) =>

{

// …

if (someCondition)

{

loop.Stop();

return;

}

// …

while (true)

{

if (loop.IsStopped) return;

// …

}

});

Break is very similar to Stop, except Break provides additional guarantees. Whereas Stop informs the loop control

logic that no more iterations need be run, Break informs the control logic that no iterations after the current one

need be run (for example, where the iteration number is higher or where the data comes after the current

element in the data source), but that iterations prior to the current one still need to be run. It doesn’t guarantee

that iterations after the current one haven’t already run or started running, though it will try t o avoid more starting

after the current one. Break may be called from multiple iterations, and the lowest iteration from which Break was

called is the one that takes effect; this iteration number can be retrieved from the ParallelLoopState’s

LowestBreakIteration property, a nullable value. ParallelLoopResult offers a similar LowestBreakIteration

property.

Patterns of Parallel Programming Page 20

This leads to a decision matrix that can be used to interpret a ParallelLoopResult:

.

IsCompleted == true

o

All iterations were processed.

o

If IsCompleted == true, LowestBreakIteration.HasValue will be false.

.

IsCompleted == false && LowestBreakIteration.HasValue == false

o

Stop was used to exit the loop early

.

IsCompleted == false && LowestBreakIteration.HasValue == true

o

Break was used to exit the loop early, and LowestBreakIteration.Value contains the lowest

iteration from which Break was called.

Here is an example of using Break with a loop:

C#

var output = new TResult[N];

var loopResult = Parallel.For(0, N, (int i, ParallelLoopState loop) =>

{

if (someCondition)

{

loop.Break();

return;

}

output[i] = Compute(i);

});

long completedUpTo = N;

if (!loopResult.IsCompleted && loopResult.LowestBreakIteration.HasValue)

{

completedUpTo = loopResult.LowestBreakIteration.Value;

}

Stop is typically useful for unordered search scenarios, where the loop is looking for something and can bail as

soon as it finds it. Break is typically useful for ordered search scenarios, where all of the data up until some point in

the source needs to be processed, with that point based on some search criteria.

UNPLANNED EXIT

The previously mentioned mechanisms for exiting a loop early are based on the body of the loop performing an

action to bail out. Sometimes, however, we want an entity external to the loop to be able to request that the loop

terminate; this is known as cancellation.

Cancellation is supported in parallel loops through the new System.Threading.CancellationToken type introduced

in the .NET Framework 4. Overloads of all of the methods on Parallel accept a ParallelOptions instance, and one of

the properties on ParallelOptions is a CancellationToken. Simply set this CancellationToken property to the

CancellationToken that should be monitored for cancellation, and provide that options instance to the loop’s

invocation. The loop will monitor the token, and if it finds that cancellation has been requested, it will again stop

launching more iterations, wait for all existing iterations to complete, and then throw an

OperationCanceledException.

C#

private CancellationTokenSource _cts = new CancellationTokenSource();

Patterns of Parallel Programming

Page 21

// …

var options = new ParallelOptions { CancellationToken = _cts.Token };

try

{

Parallel.For(0, N, options, i =>

{

// …

});

}

catch(OperationCanceledException oce)

{

// … Handle loop cancellation.

}

Stop and Break allow a loop itself to proactively exit early and successfully, and cancellation allows an external

entity to the loop to request its early termination. It’s also possible for something in the loop’s body to go wrong,

resulting in an early termination of the loop that was not expected.

In a sequential loop, an unhandled exception thrown out of a loop causes the looping construct to immediately

cease. The parallel loops in the .NET Framework 4 get as close to this behavior as is possible while still being

reliable and predictable. This means that when an exception is thrown out of an iteration, the Parallel methods

attempt to prevent additional iterations from starting, though already started iterations are not forcibly

terminated. Once all iterations have ceased, the loop gathers up any exceptions that have been thrown, wraps

them in a System.AggregateException, and throws that aggregate out of the loop.

As with Stop and Break, for cases where individual operations may run for a long time (and thus may delay the

loop’s exit), it may be advantageous for iterations of a loop to be able to check whether other iterations have

faulted. To accommodate that, ParallelLoopState exposes an IsExceptional property (in addition to the

aforementioned IsStopped and LowestBreakIteration properties), which indicates whether another iteration has

thrown an unhandled exception. Iterations may cooperatively check this property, allowing a long-running

iteration to cooperatively exit early when it detects that another iteration failed.

While this exception logic does support exiting out of a loop early, it is not the recommended mechanism for doing

so. Rather, it exists to assist in exceptional cases, cases where breaking out early wasn’t an intentional part of the

algorithm. As is the case with sequential constructs, exceptions should not be relied upon for control flow.

Note, too, that this exceptions behavior isn’t optional. In the face of unhandled exceptions, there’s no way to tell

the looping construct to allow the entire loop to complete execution, just as there’s no built-in way to do that with

a serial for loop. If you wanted that behavior with a serial for loop, you’d likely end up writing code like the

following:

C#

var exceptions = new Queue<Exception>();

for (int i = 0; i < N; i++)

{

try

{

// … Loop body goes here.

}

catch (Exception exc) { exceptions.Enqueue(exc); }

}

if (exceptions.Count > 0) throw new AggregateException(exceptions);

Patterns of Parallel Programming Page 22

If this is the behavior you desire, that same manual handling is also possible using Parallel.For:

C#

var exceptions = new ConcurrentQueue<Exception>();

Parallel.For(0, N, i =>

{

try

{

// … Loop body goes here.

}

catch (Exception exc) { exceptions.Enqueue(exc); }

});

if (!exceptions.IsEmpty) throw new AggregateException(exceptions);

EMPLOYING MULTIPLE EX IT STRATEGIES

It’s possible that multiple exit strategies could all be employed together, concurrently; we’re dealing with

parallelism, after all. In such cases, exceptions always win: if unhandled exceptions have occurred, the loop will

always propagate those exceptions, regardless of whether Stop or Break was called or whether cancellation was

requested.

If no exceptions occurred but the CancellationToken was signaled and either Stop or Break was used, there’s a

potential race as to whether the loop will notice the cancellation prior to exiting. If it does, the loop will exit with

an OperationCanceledException. If it doesn’t, it will exit due to the Stop/Break as explained previously.

However, Stop and Break may not be used together. If the loop detects that one iteration called Stop while

another called Break, the invocation of whichever method ended up being invoked second will result in an

exception being thrown. This is enforced due to the conflicting guarantees provided by Stop and Break.

For long running iterations, there are multiple properties an iteration might want to check to see whether it should

bail early: IsStopped, LowestBreakIteration, IsExceptional, and so on. To simplify this, ParallelLoopState also

provides a ShouldExitCurrentIteration property, which consolidates all of those checks in an efficient manner. The

loop itself checks this value prior to invoking additional iterations.

P A R A L L E L E N U M E R A B L E . F O R A L L

Parallel LINQ (PLINQ), exposed from System.Core.dll in the .NET Framework 4, provides a parallelized

implementation of all of the .NET Framework standard query operators. This includes Select (projections), Where

(filters), OrderBy (sorting), and a host of others. PLINQ also provides several additional operators not present in its

serial counterpart. One such operator is AsParallel, which enables parallel processing of a LINQ-to-Objects query.

Another such operator is ForAll.

Partitioning of data has already been discussed to some extent when discussing Parallel.For and Parallel.ForEach,

and merging will be discussed in greater depth later in this document. Suffice it to say, however, that to process an

input data set in parallel, portions of that data set must be distributed to each thread partaking in the processing,

Patterns of Parallel Programming Page 23

and when all of the processing is complete, those partitions typically need to be merged back together to form the

single output stream expected by the caller:

C#

List<InputData> inputData = …;

foreach (var o in inputData.AsParallel().Select(i => new OutputData(i)))

{

ProcessOutput(o);

}

Both partitioning and merging incur costs, and in parallel programming, we strive to avoid such costs as they’re

pure overhead when compared to a serial implementation. Partitioning can’t be avoided if data must be processed

in parallel, but in some cases we can avoid merging, such as if the work to be done for each resulting item can be

processed in parallel with the work for every other resulting item. To accomplish this, PLINQ provides the ForAll

operator, which avoids the merge and executes a delegate for each output element:

C#

List<InputData> inputData = …;

inputData.AsParallel().Select(i => new OutputData(i)).ForAll(o =>

{

ProcessOutput(o);

});

A N T I -P A T T E R N S

Superman has his kryptonite. Matter has its anti-matter. And patterns have their anti-patterns. Patterns prescribe

good ways to solve certain problems, but that doesn’t mean they’re not without potential pitfalls. There are

several potential problems to look out for with Parallel.For, Parallel.ForEach, and ParallelEnumerable.ForAll.

S H A R E D D A T A

The new parallelism constructs in the .NET Framework 4 help to alleviate most of the boilerplate code you’d

otherwise have to write to parallelize delightfully parallel problems. As you saw earlier, the amount of code

necessary just to implement a simple and naïve MyParallelFor implementation is vexing, and the amount of code

required to do it well is reams more. These constructs do not, however, automatically ensure that your code is

thread-safe. Iterations within a parallel loop must be independent, and if they’re not independent, you must

ensure that the iterations are safe to execute concurrently with each other by doing the appropriate

synchronization.

I T E R A T I O N V A R I A N T S

In managed applications, one of the most common patterns used with a for/For loop is iterating from 0 inclusive to

some upper bound (typically exclusive in C# and inclusive in Visual Basic). However, there are several variations on

this pattern that, while not nearly as common, are still not rare.

DOWNWARD ITERATION

Patterns of Parallel Programming Page 24

It’s not uncommon to see loops iterating down from an upper-bound exclusive to 0 inclusive:

C#

for(int i=upperBound-1; i>=0; –i) { /*…*/ }

Such a loop is typically (though not always) constructed due to dependencies between the iterations; after all, if all

of the iterations are independent, why write a more complex form of the loop if both the upward and downward

iteration have the same results?

Parallelizing such a loop is often fraught with peril, due to these likely dependencies between iterations. If there

are no dependencies between iterations, the Parallel.For method may be used to iterate from an inclusive lower

bound to an exclusive upper bound, as directionality shouldn’t matter: in the extreme case of parallelism, on a

machine with upperBound number of cores, all iterations of the loop may execute concurrently, and direction is

irrelevant.

When parallelizing downward-iterating loops, proceed with caution. Downward iteration is often a sign of a less

than delightfully parallel problem.

STEPP ED ITERATION

Another pattern of a for loop that is less common than the previous cases, but still is not rare, is one involving a

step value other than one. A typical for loop may look like this:

C#

for (int i = 0; i < upperBound; i++) { /*…*/ }

But it’s also possible for the update statement to increase the iteration value by a different amount: for example to

iterate through only the even values between the bounds:

C#

for (int i = 0; i < upperBound; i += 2) { /*…*/ }

Parallel.For does not provide direct support for such patterns. However, Parallel can still be used to implement

such patterns. One mechanism for doing so is through an iterator approach like that shown earlier for iterating

through linked lists:

C#

private static IEnumerable<int> Iterate(

int fromInclusive, int toExclusive, int step)

{

for (int i = fromInclusive; i < toExclusive; i += step) yield return i;

}

A Parallel.ForEach loop can now be used to perform the iteration. For example, the previous code snippet for

iterating the even values between 0 and upperBound can be coded as:

C#

Parallel.ForEach(Iterate(0, upperBound, 2), i=> { /*…*/ });

Patterns of Parallel Programming Page 25

As discussed earlier, such an implementation, while straightforward, also incurs the additional costs of forcing the

Parallel.ForEach to takes locks while accessing the iterator. This drives up the per-element overhead of

parallelization, demanding that more work be performed per element to make up for the increased overhead in

order to still achieve parallelization speedups.

Another approach is to do the relevant math manually. Here is an implementation of a ParallelForWithStep loop

that accepts a step parameter and is built on top of Parallel.For:

C#

public static void ParallelForWithStep(

int fromInclusive, int toExclusive, int step, Action<int> body)

{

if (step < 1)

{

throw new ArgumentOutOfRangeException(“step”);

}

else if (step == 1)

{

Parallel.For(fromInclusive, toExclusive, body);

}

else // step > 1

{

int len = (int)Math.Ceiling((toExclusive -fromInclusive) / (double)step);

Parallel.For(0, len, i => body(fromInclusive + (i * step)));

}

}

This approach is less flexible than the iterator approach, but it also involves significantly less overhead. Threads are

not bottlenecked serializing on an enumerator; instead, they need only pay the cost of a small amount of math

plus an extra delegate invocation per iteration.

V E R Y S M A L L L O O P B O D I E S

As previously mentioned, the Parallel class is implemented in a manner so as to provide for quality load balancing

while incurring as little overhead as possible. There is still overhead, though. The overhead incurred by Parallel.For

is largely centered around two costs:

1)

Delegate invocations. If you squint at previous examples of Parallel.For, a call to Parallel.For looks a lot

like a C# for loop or a Visual Basic For loop. Don’t be fooled: it’s still a method call. One consequence of

this is that the “body” of the Parallel.For “loop” is supplied to the method call as a delegate. Invoking a

delegate incurs approximately the same amount of cost as a virtual method call.

2)

Synchronization between threads for load balancing. While these costs are minimized as much as

possible, any amount of load balancing will incur some cost, and the more load balancing employed, the

more synchronization is necessary.

For medium to large loop bodies, these costs are largely negligible. But as the size of the loop’s body decreases,

the overheads become more noticeable. And for very small bodies, the loop can be completely dominated by this

overhead’s cost. To support parallelization of very small loop bodies requires addressing both #1 and #2 above.

One pattern for this involves chunking the input into ranges, and then instead of replacing a sequential loop with a

parallel loop, wrapping the sequential loop with a parallel loop.

Patterns of Parallel Programming

Page 26

The System.Concurrent.Collections.Partitioner class provides a Create method overload that accepts an integral

range and returns an OrderablePartitioner<Tuple<Int32,Int32>> (a variant for Int64 instead of Int32 is also

available):

C#

public static OrderablePartitioner<Tuple<long, long>> Create(

long fromInclusive, long toExclusive);

Overloads of Parallel.ForEach accept instances of Partitioner<T> and OrderablePartitioner<T> as sources, allowing

you to pass the result of a call to Partitioner.Create into a call to Parallel.ForEach. For now, think of both

Partitioner<T> and OrderablePartitioner<T> as an IEnumerable<T>.

The Tuple<Int32,Int32> represents a range from an inclusive value to an exclusive value. Consider the following

sequential loop:

C#

for (int i = from; i < to; i++)

{

// … Process i.

}

We could use a Parallel.For to parallelize it as follows:

C#

Parallel.For(from, to, i =>

{

// … Process i.

});

Or, we could use Parallel.ForEach with a call to Partitioner.Create, wrapping a sequential loop over the range

provided in the Tuple<Int32, Int32>, where the inclusiveLowerBound is represented by the tuple’s Item1 and

where the exclusiveUpperBound is represented by the tuple’s Item2:

C#

Parallel.ForEach(Partitioner.Create(from, to), range =>

{

for (int i = range.Item1; i < range.Item2; i++)

{

// … process i

}

});

While more complex, this affords us the ability to process very small loop bodies by eschewing some of the

aforementioned costs. Rather than invoking a delegate for each body invocation, we’re now amortizing the cost of

the delegate invocation across all elements in the chunked range. Additionally, as far as the parallel loop is

concerned, there are only a few elements to be processed: each range, rather than each index. This implicitly

decreases the cost of synchronization because there are fewer elements to load-balance.

While Parallel.For should be considered the best option for parallelizing for loops, if performance measurements

show that speedups are not being achieved or that they’re smaller than expected, you can try an approach like the

one shown using Parallel.ForEach in conjunction with Partitioner.Create.

Patterns of Parallel Programming Page 27

T O O F I N E -G R A I N E D , T O O C O A R S E G R A I N E D

The previous anti-pattern outlined the difficulties that arise from having loop bodies that are too small. In addition

to problems that implicitly result in such small bodies, it’s also possible to end up in this situation by decomposing

the problem to the wrong granularity.

Earlier in this section, we demonstrated a simple parallelized ray tracer:

C#

void RenderParallel(Scene scene, Int32[] rgb)

{

Camera camera = scene.Camera;

Parallel.For(0, screenHeight, y =>

{

int stride = y * screenWidth;

for (int x = 0; x < screenWidth; x++)

{

Color color = TraceRay(

new Ray(camera.Pos, GetPoint(x, y, camera)), scene, 0);

rgb[x + stride] = color.ToInt32();

}

});

}

Note that there are two loops here, both of which are actually safe to parallelize:

C#

void RenderParallel(Scene scene, Int32[] rgb)

{

Camera camera = scene.Camera;

Parallel.For(0, screenHeight, y =>

{

int stride = y * screenWidth;

Parallel.For(0, screenWidth, x =>

{

Color color = TraceRay(

new Ray(camera.Pos, GetPoint(x, y, camera)), scene, 0);

rgb[x + stride] = color.ToInt32();

});

});

}

The question then arises: why and when someone would choose to parallelize one or both of these loops? There

are multiple, competing principles. On the one hand, the idea of writing parallelized software that scales to any

number of cores you throw at it implies that you should decompose as much as possible, so that regardless of the

number of cores available, there will always be enough work to go around. This principle suggests both loops

should be parallelized. On the other hand, we’ve already seen the performance implications that can result if

there’s not enough work inside of a parallel loop to warrant its parallelization, implying that only the outer loop

should be parallelized in order to maintain a meaty body.

Patterns of Parallel Programming Page 28

The answer is that the best balance is found through performance testing. If the overheads of parallelization are

minimal as compared to the work being done, parallelize as much as possible: in this case, that would mean

parallelizing both loops. If the overheads of parallelizing the inner loop would degrade performance on most

systems, think twice before doing so, as it’ll likely be best only to parallelize the outer loop/

There are of course some caveats to this (in parallel programming, there are caveats to everything; there are

caveats to the caveats). Parallelization of only the outer loop demands that the outer loop has enough work to

saturate enough processors. In our ray tracer example, what if the image being ray traced was very wide and short,

such that it had a small height? In such a case, there may only be a few iterations for the outer loop to parallelize,

resulting in too coarse-grained parallelization, in which case parallelizing the inner loop could actually be

beneficial, even if the overheads of parallelizing the inner loop would otherwise not warrant its parallelization.

Another option to consider in such cases is flattening the loops, such that you end up with one loop instead of two.

This eliminates the cost of extra partitions and merges that would be incurred on the inner loop’s parallelization:

C#

void RenderParallel(Scene scene, Int32[] rgb)

{

int totalPixels = screenHeight * screenWidth;

Camera camera = scene.Camera;

Parallel.For(0, totalPixels, i =>

{

int y = i / screenWidth, x = i % screenWidth;

Color color = TraceRay(

new Ray(camera.Pos, GetPoint(x, y, camera)), scene, 0);

rgb[i] = color.ToInt32();

});

}

If in doing such flattening the body of the loop becomes too small (which given the cost of TraceRay in this

example is unlikely), the pattern presented earlier for very small loop bodies may also be employed:

C#

void RenderParallel(Scene scene, Int32[] rgb)

{

int totalPixels = screenHeight * screenWidth;

Camera camera = scene.Camera;

Parallel.ForEach(Partitioner.Create(0, totalPixels), range =>

{

for (int i = range.Item1; i < range.Item2; i++)

{

int y = i / screenWidth, x = i % screenWidth;

Color color = TraceRay(

new Ray(camera.Pos, GetPoint(x, y, camera)), scene, 0);

rgb[i] = color.ToInt32();

}

});

}

N O N -T H R E A D -S A F E I L I S T < T > I M P L E M E N T A T I O N S

Patterns of Parallel Programming Page 29

Both PLINQ and Parallel.ForEach query their data sources for several interface implementations. Accessing an

IEnumerable<T> incurs significant cost, due to needing to lock on the enumerator and make virtual methods calls

to MoveNext and Current for each element. In contrast, getting an element from an IList<T> can be done without

locks, as elements of an IList<T> are independent. Thus, both PLINQ and Parallel.ForEach automatically use a

source’s IList<T> implementation if one is available.

In most cases, this is the right decision. However, in very rare cases, an implementation of IList<T> may not be

thread-safe for reading due to the get accessor for the list’s indexer mutating shared state. There are two

predominant reasons why an implementation might do this:

1.

The data structures stores data in a non-indexible manner, such that it must traverse the data structure

to find the requested index. In such a case, the data structure may try to amortize the cost of access by

keeping track of the last element accessed, assuming that accesses will occur in a largely sequential

manner, making it cheaper to start a search from the previously accessed element than starting from

scratch. Consider a theoretical linked list implementation as an example. A linked list does not typically

support direct indexing; rather, if you want to access the 42nd element of the list, you need to start at the

beginning, prior to the head, and move to the next element 42 times. As an optimization, the list could

maintain a reference to the most recently accessed element. If you accessed element 42 and then

element 43, upon accessing 42 the list would cache a reference to the 42nd element, thus making access

to 43 a single move next rather than 43 of them from the beginning. If the implementation doesn’t take

thread-safety into account, these mutations are likely not thread-safe.

2.

Loading the data structure is expensive. In such cases, the data can be lazy-loaded (loaded on first

access) to defer or avoid some of the initialization costs. If getting data from the list forces initialization,

then mutations could occur due to indexing into the list.

There are only a few, obscure occurrences of this in the .NET Framework. One

example is System.Data.Linq.EntitySet<TEntity>. This type implements

IList<TEntity> with support for lazy loading, such that the first thing its indexer’s get